10/31/2010. Remarks by Johan Visschedijk: "Conceived as a research vehicle to obtain experience for the design of future high-speed combat aircraft, the X-3 had one of the longest gestation periods of any Douglas-designed aircraft. As early as 1941, at the request of the USAAF, Douglas had begun to investigate supersonic flight and on December 30, 1943, the company had been specifically asked to determine the feasibility of designing an aeroplane capable of flying at sustained speeds beyond Mach 1.

Following a series of conferences held throughout 1944 between Air Technical Service Command and Douglas representatives, a Phase I proposal was submitted in January 1945. With this proposal plans were made to undertake initial design, prepare preliminary specifications, conduct wind-tunnel model testing, build a mockup and draft detailed specifications for this research aircraft. However, even though this proposal was endorsed by the USAAF on May 30 and a contract signed by the Secretary of War on June 20, 1945, the aircraft did not fly until September 20, 1952.

The basic performance requirements included a top speed of Mach 2 at 30,000 ft (9,145 m) and an endurance of 30 minutes, while from the onset it was felt that the aircraft should not be catapulted or carried aloft by a mother aeroplane but should be able to take off and land under its own power on a conventional runway. The task thus facing the design team led by Frank N. Fleming was particularly arduous and many configurations and power plant installations were proposed and studied until the late summer of 1948 when a final configuration was selected.

During this three-year initial design phase several power plant alternatives were evaluated, including single- and twin-jet configurations with or without thrust augmentation by means of either main engine afterburner, auxiliary rocket engines, pulse jets or ramjets during the transonic regime. Wing configurations under consideration included delta and low aspect ratio designs while fuselage cross-section was kept at a minimum to reduce aerodynamic drag and kinetic heating.

Difficulties slowing progress stemmed from the limited endurance of most of the proposed configurations, from inexperience in designing structures capable of absorbing the heat generated during sustained flight at twice the speed of sound and from the need to devise a safe means of emergency escape for the pilot.

Finally, the Douglas Model 499C configuration showed considerable promise and in August 1948 the USAF authorized construction of a detailed full-size mockup. At this stage the aircraft was anticipated to have a gross weight of around 23,000 lb (10,433 kg) and was to be powered by two 4,500 lb (2,041 kg) thrust – 6,000 lb (2,722 kg) thrust with afterburner – Westinghouse XJ46-WE-1 turbojets with which a 10-minute endurance at Mach 2 and 35,000 ft (10,670 m) was considered possible. It was also planned that the aircraft would be fitted with a jettisonable nose and pressurized cockpit section to facilitate emergency pilot escape at high speeds.

Mockup inspection took place between December 6 and 9, 1948, by which time the jettisonable nose section, which in wind-tunnel tests had been found to create aircraft instability, had been replaced by a conventional nose section with downward-operating pilot ejector seat. The mockup inspection team, which included Major Charles E. Yeager who on October 14, 1947, had become the first pilot to exceed the speed of sound in level flight, was impressed by the quality of workmanship and great detail shown in the mockup, these being indicative of the amount of research and engineering effort expended during the course of the initial Phase I contract.

There were 96 comments submitted by the inspection team but this was not considered excessive in view of the complexity and experimental nature of the aircraft. On the basis of the mockup inspection team's report and from additional data submitted by the manufacturers, the USAF approved on 30 June, 1949, Phase II of the project and ordered two flying prototypes (s/n

49-2892 and 49-2893) and one fatigue and structural test airframe.

During the course of the next year there were several developments affecting the future of the program. The most significant change was that the developed Westinghouse J46 required an increase in diameter beyond the limits imposed by the narrow cross-section of the X-3 fuselage. Consequently, it was decided to install a pair of 3,370 lb (1,529 kg) thrust – 4,900 lb (2,223 kg) thrust with afterburner – Westinghouse XJ34-WE-17 turbojets on the first prototype and to suspend work temporarily on the second.

The reduction in total available thrust of just over 18% became a source of major concern and NACA was asked to study ways of increasing the power of the XJ34-WE-17. Studies were made of water injection and liquid ammonia injection systems but neither proved successful enough for adoption and, consequently, the X-3 was left seriously underpowered. NACA contribution to the X-3 program was, however, not limited to power plant improvement studies but also included free-fall tests with a quarter-scale model which disclosed the need to modify and strengthen the boom supporting the tail surfaces.

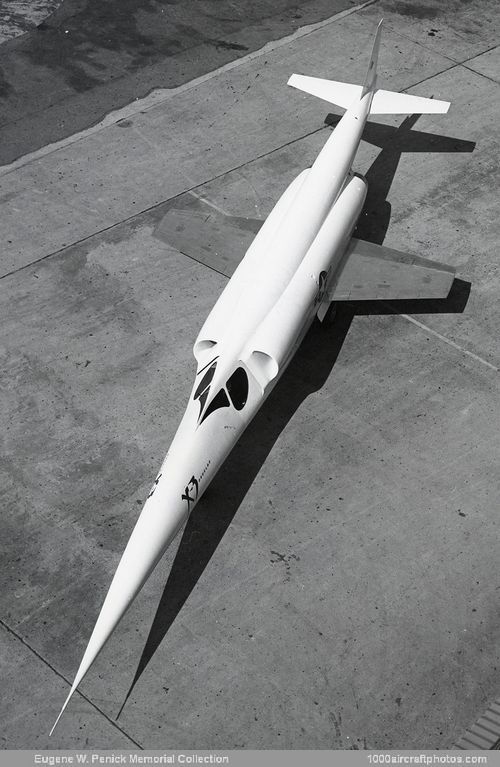

While all this work was being done Douglas suggested and obtained approval for the substitution of 629 lb (285 kg) of titanium instead of the 1,024 lb (464 kg) of stainless steel in various critical airframe components. Construction of the single X-3 prototype-the second test vehicle being cancelled due to power plant problems-was begun in early 1950 and completed in September 1951, seven years and nine months after initial discussions. The aircraft had a slender fuselage with an extremely long tapered nose containing most of the 1,200 lb (544 kg) of instrumentation, much of it specially designed for the X-3 and supplied by NACA.

The pressurized cockpit was fitted with a downward ejector seat which was also an electrically-operated lift for the pilot's use on the ground. For emergency evacuation on the ground the side cockpit windows could be jettisoned by the pilot or ground crew. The two turbojets were mounted side-by-side midway in the fuselage and were fed from two fuel tanks, one behind the pilot and beneath the air ducts and one located in the tail boom above the downward sloping afterburners.

The diminutive wings had a span of only 22 ft 8.25 in (6.91 m), an aspect ratio of 3 and a 4.5% thick modified diamond airfoil, and were fitted with split trailing edge flaps. The tricycle landing gear retracted into the fuselage.

Due to a number of problems, particularly leakages in the fuel system, flight trials were delayed a further year following the completion of the aircraft.